Whether you are devising plans, making decisions or filling in a canvas, often we work with a mixture of things that we have evidence for and things that are just ideas.

Table of Contents

This is not a bad thing, however, it can be risky to mistake ideas for evidence.

If you falsely believe something to be true, you are less inclined to challenge it. Contrarily, if the evidence was hidden from you, you might work on validating something that was already known to be true: a waste of time.

In this article, I will give you a trick to easily spot the difference between ideas and (ideas with) evidence.

Evidence and ideas

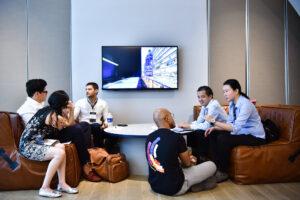

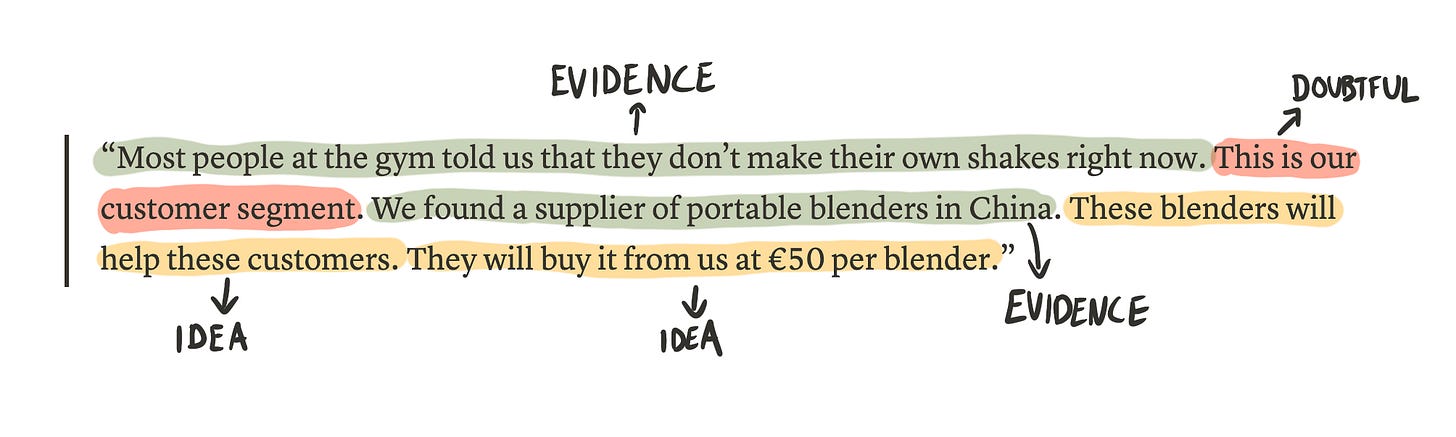

How do ideas and evidence pop up? Let’s check out this example from a portable blender startup I briefly mentored. This startup aimed to launch portable blenders, a product that’s already popular in the US, in Europe.

They had a plan to get into this market. In a mentoring session, they made five claims with varying empirical backing:

Take apart the sentences

People at the gym told us → ✅ Evidence

The verb ‘to tell’ shows the source of evidence about the current behaviour. Unless these gym-goers are lying, I’m likely to say that this claim got some evidence behind it.

This is our customer segment → ⁉️ Doubtful → 💡 Idea

The customer segment of people going to the gym exists. However, without any sales, we can’t say evidentially these are ‘your’ customers yet. Language of the ‘are/is’ nature is always tricky. It begs for more evidence and information. Sales numbers would’ve helped here, but they didn’t have any yet. Therefore, this ‘doubtful’ claim is an idea only.

We found a supplier → ✅ Evidence

The verb ‘find’ suggests the existence of this supplier. This sentence doesn’t show a supplier, but they told me they were emailing with one. However, before a deal is made, it’s not ‘your’ supplier yet. Still, I would argue it’s easier to make a supplier yours than a making a customer segment yours.

At first, you always want to know ‘does this type of thing exist’, in this case, a portable blender supplier. After that, you want evidence that you can make it yours. This shows that evidence is a spectrum, not a boolean.

These blenders will help these customers → 💡 Idea

Arguably true, especially as portable blenders are big in the States. However, there aren’t many portable blenders in Europe. Let alone this startup’s own portable blenders. It’s unclear whether their intended target group’s problem will be solved by this solution. Predictive verbs, such as ‘will’, hint at ideas. This relates to the idea of the past holds more truth.

They will buy the blender for €50 → 💡 Idea

There is no observed behaviour yet. There’s a hint of a pricing strategy in that statement, yet no evidence of if these potential customers actually will buy it. Just an idea.

Check the origin verbs

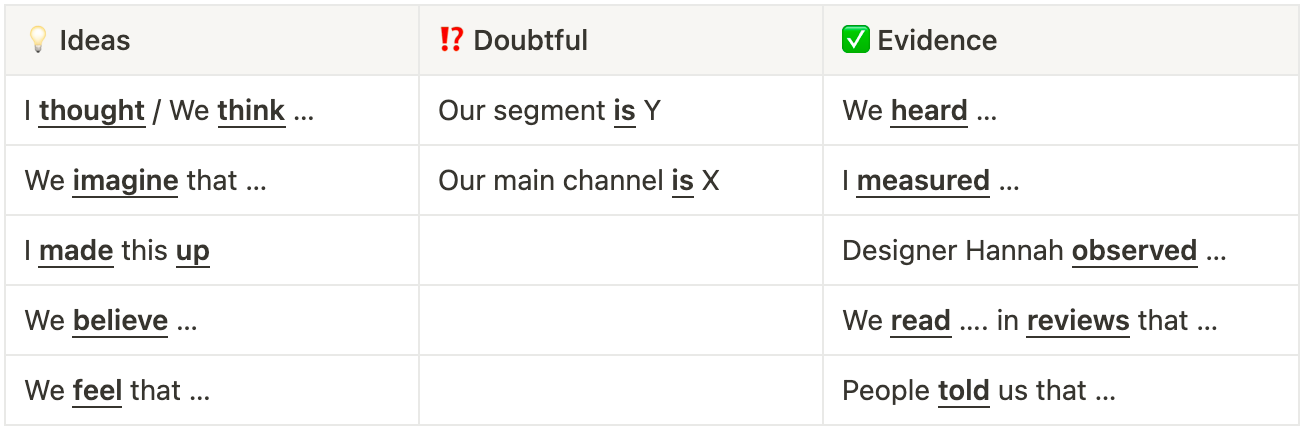

Above, we see three archetypes: ideas, evidence and doubtful instances. Founders constantly jump back and forth between evidence and ideas.

A great way to tell the difference is the origin verbs. These verbs hold the source of the claim of information. To tell evidence from ideas, pay special attention to the origin verbs.

If there’s no clear origin verb, ask the speaker to choose one. I often ask: ‘Did you hear this, notice this, or did you think of this?’ You will learn soon enough.

On doubtful: They can flick both ways. ‘Our channel is social ads as we made 500 sales’ is different than ‘Our customer segment is gym goers as we found people at the gym without a portable blender’. It takes close inspection.

🔥 Jeroen’s spicy hot take

What I tried to show is a certain inflexion that I notice in practice. Don’t take the above table too literally, but try to digest the direction that I’m giving.

Build your own sense of what words are related to ideas and what words are related to evidence.